Teddy Roosevelt was not your typical President. Just for fun, he would memorize obscure poetry and dense state documents and recite them on cue. He would send to Congress book-length messages, complete with graphic illustrations. During his “spare” time, he was a professional author, writing twenty-three volumes, numerous scientific articles, and roughly fifty thousand letters.

While he wasn’t writing or running the United States, he enjoyed hunting and horseback riding. During a particularly exhausting jaunt, his horse tripped over a wall, breaking Roosevelt’s left arm and smashing his face. Roosevelt was unfazed. He kept riding his horse and later wrote to his friend, Henry Cabot Lodge, that he didn’t “grudge the broken arm a bit . . . I’m always ready to pay the piper when I’ve had a good dance; and every now and then I like to drink the wine of life with brandy in it.”

Even with physical exercise, Teddy mixed his metaphorical wine with brandy. Here’s how Edmund Morris describes his exercise habits in his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt:

“Senator Henry Cabot Lodge has been heard yelling irritably at a portly object swaying in the sky, ‘Theodore! if you knew how ridiculous you look on top of that tree, you would come down at once.’ On winter evenings in Rock Creek Park, strollers may observe the President of the United States wading pale and naked into the ice-clogged stream, followed by shivering members of his Cabinet. Thumping noises in the White House library indicate that Roosevelt is being thrown around the room by a Japanese wrestler; a particularly seismic crash, which makes the entire mansion tremble, signifies that Secretary Taft has been forced to join in the fun.”

His eccentricities made Teddy, in his own words, “ardent friends” and plenty of “bitter enemies.” Before he became President, one magazine wished him “a gradual and gentle awakening,” telling him that he is “not the timber of which Presidents are made.”

But Teddy marched on, holding steadfast to his larger-than-life personality, and riding it all the way to the White House.

* * *

When Arnold Schwarzenegger was trying to break into the movie business, the agents all turned him down.

“Look, you have an accent that scares people,” said a representative from ICM Partners. “You have a body that’s too big for movies. You have a name that won’t even fit on a movie poster. Everything about you is strange.”

At first, Schwarzenegger caved in. He began taking accent removal lessons to become more mainstream. His speech coach would force him to say “A fine wine grows on the vine” and the “sink is made of zinc” on repeat–an exceedingly difficult feat for a native speaker of German, which doesn’t have a w sound, and different pronunciations for the s and z in English.

Eventually, Schwarzenegger dropped his accent coach, along with his efforts to fit in, and adopted Muhammad Ali as his role model. In his autobiography, Schwarzenegger explains why he decided to follow in Ali’s footsteps:

“What separated him from other heavyweights wasn’t only his boxing genius–the rope-a-dope, the float like a butterfly, sting like a bee-but that he went his own way, becoming a Muslim, changing his name, sacrificing his championship title by refusing military service” in Vietnam.

Like Ali, Schwarzenegger began to embrace rather than eliminate the qualities that set him apart from others–his barely comprehensible accent, his distinctive name, his cheesy one-liners (“I’ll be back”), his Republicanism in deeply liberal Hollywood, and his ridiculous body. These eccentricities quickly turned into assets and made him an inimitable action hero (even though he hasn’t always been remarkable for the right reasons).

* * *

When Sofia Vergara first tried to leave Univision and enter mainstream Hollywood, she was advised to get rid of her accent.

But this was no easy feat. Here’s Vergara on her struggles:

“I hired the speech coach, and you have to work so much. It’s exhausting. It’s also boring. And I have a bad ear, you know? I’ve been in this country for 20-something years and I still sound like this. . . . So I was going to auditions and the only thing I could focus on was the position of the tongue. I was not acting. And then I thought, If I can’t get a job with my accent, this is not a job for me.”

This was a turning point for Vergara. Instead of caving into societal pressures to conform to the Hollywood stereotype and Americanize herself, she did the opposite. She embraced everything that made her stick out like a sore thumb–her Colombian roots, her physique, and her heavy accent. These characteristics not only made her remarkable, but also allowed her to focus on the one skill that mattered: acting.

* * *

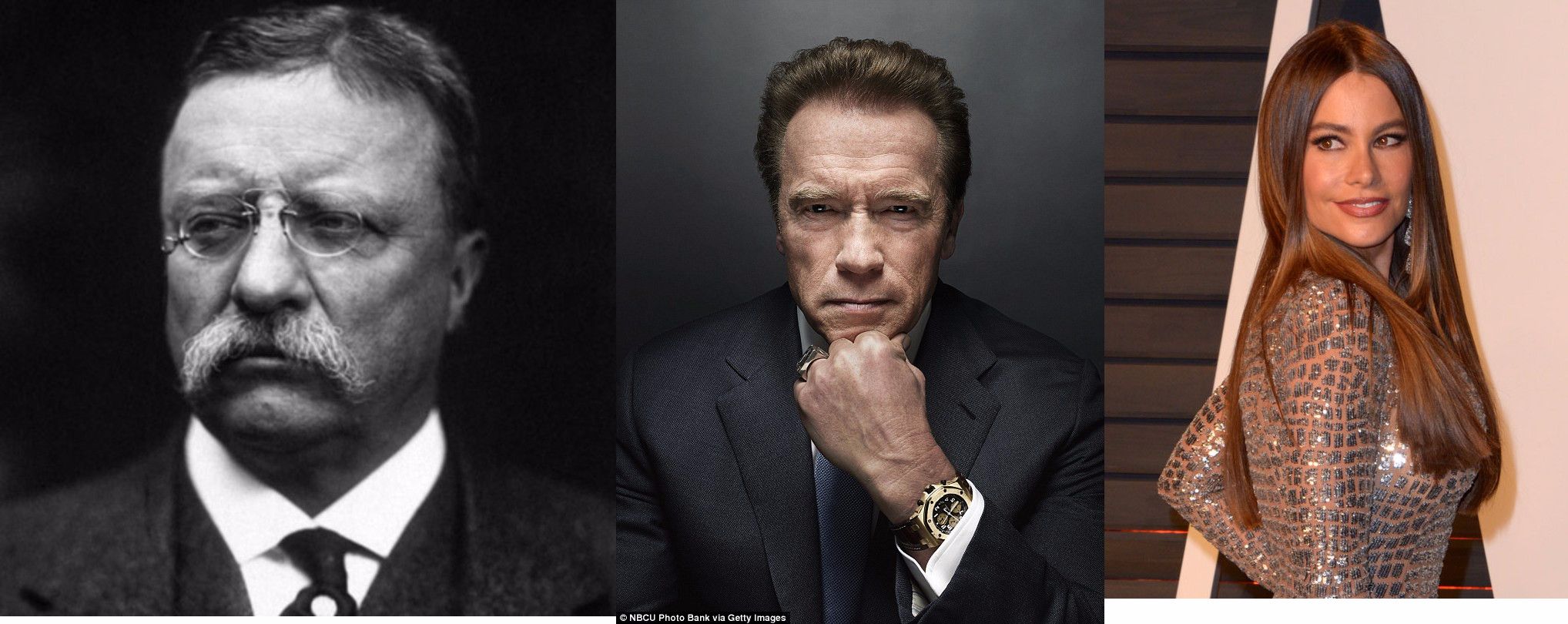

What forms the unlikely bond between Teddy, Arnold, and Sofia is contrarian thinking. They went from being a nobody to a household name precisely because they bucked conventional wisdom on what a mainstream president, actor, or actress should do. They refused to blend. They refused to conform. They stuck out in ways that made them memorable. They were unapologetic.

Their life stories hold important lessons for us all. We’re all in a race to the center, trying to look like the others, sound like the others, and act like the others. Our internal narrative and the 100-decibel sirens of our conformist society tell us to play it safe and follow the herd. But the way to get ahead is to channel your inner Teddy, Sofia, and Arnold, and embrace, rather than conceal, your differences.

Bold