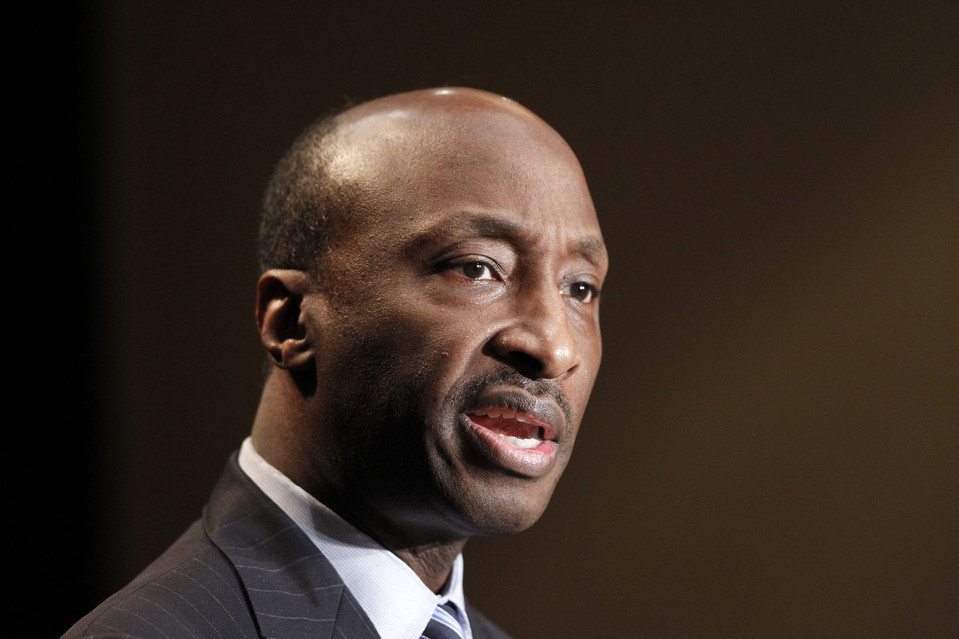

Merck’s CEO Kenneth Frazier, one of the country’s most prominent African-American executives, made headlines when he quit President Donald Trump’s American Manufacturing Council. His resignation came in response to President Trump’s attribution of blame to both sides in the violence that ensued in Charlottesville, Virginia.

In many ways, Frazier’s story is quintessentially American. The son of a janitor, Frazier grew up in inner city Philadelphia and climbed to the top against all odds, graduating from Penn State and then Harvard Law School. After practicing law at a private firm, he joined Merck as corporate counsel and eventually became its CEO.

There’s much to admire about Frazier, but for the purposes of this article, I’ll focus on a contrarian corporate strategy he championed at Merck. This strategy has the potential to catapult your business or your life to the next level.

Like most executives, Frazier wanted to promote innovation. But unlike most executives who simply ask their employees “to innovate,” Frazier asked them to do something they had never done before.

Generate ideas to destroy Merck.

Following Frazier’s lead, Merck executives pretended to be one of Merck’s top competitors and found numerous ways to back Merck into a corner and eliminate any competitive advantage it enjoyed. They then reversed their roles, went back to being Merck employees, and devised strategies to avert these threats.

In corporate boardrooms across the United States, the same cliche questions are asked to prompt innovation: “What’s the next big thing?,” or, my least favorite, “Let’s think outside the box.”

To come up with answers to these cliches, executives look in the rear view mirror and rely on the same worn-out methods or, even worse, copy-the-competitor strategies. It’s no wonder that the resulting innovations aren’t innovations at all. They’re at best insignificant deviations from the status quo.

In contrast, Frazier’s contrarian “kill the company” exercise flips the innovation question upside down and forces executives to deploy new neural pathways. The strategy requires a radically new way of thinking that enables companies to see opportunities for innovation that may have been hiding in their blind spots.

Frazier’s strategy has another benefit that Adam Grant highlights in his book, The Originals:

This “kill the company” exercise is powerful because it reframes a gain-framed activity in terms of losses. When deliberating about innovation opportunities, the leaders weren’t inclined to take risks. When they considered how their competitors could put them out of business, they realized that it was a risk not to innovate. The urgency of innovation was apparent.

The “kill the company” exercise isn’t just for mega-corporations. You can employ variations of it in your own life by asking questions along the lines of the following:

Why might my boss fire me?

Why is this prospective employer justified in not hiring me?

Why are customers making the right decision by buying from our competitors?

In answering these questions, avoid superficial answers that treat them like that dreadful interview inquiry, “Tell me about your weaknesses,” which tends to induce humblebragging (“I work too hard”). Instead, really get into the shoes of the people who might fire you, refuse to hire you, or buy from your competitors.

Ask yourself: Why are they making that choice?

It’s not because they’re stupid. It’s not because they’re wrong and you’re right. It’s because they see something that you’re missing. It’s because they believe something that you don’t believe. And you can’t change that worldview or that belief by calling the same plays from the same old playbook.

Once you’ve got a good answer to these questions, switch perspectives like the Merck executives and find ways to defend against these potential threats.

Counterintuitively, the best way to catapult your life or your business might be to find ways to destroy it first.

Merck’s CEO Kenneth Frazier, one of the country’s most prominent African-American executives, made headlines when he quit President Donald Trump’s American Manufacturing Council. His resignation came in response to President Trump’s attribution of blame to both sides in the violence that ensued in Charlottesville, Virginia.

In many ways, Frazier’s story is quintessentially American. The son of a janitor, Frazier grew up in inner city Philadelphia and climbed to the top against all odds, graduating from Penn State and then Harvard Law School. After practicing law at a private firm, he joined Merck as corporate counsel and eventually became its CEO.

There’s much to admire about Frazier, but for the purposes of this article, I’ll focus on a contrarian corporate strategy he championed at Merck. This strategy has the potential to catapult your business or your life to the next level.

Like most executives, Frazier wanted to promote innovation. But unlike most executives who simply ask their employees “to innovate,” Frazier asked them to do something they had never done before.

Generate ideas to destroy Merck.

Following Frazier’s lead, Merck executives pretended to be one of Merck’s top competitors and found numerous ways to back Merck into a corner and eliminate any competitive advantage it enjoyed. They then reversed their roles, went back to being Merck employees, and devised strategies to avert these threats.

In corporate boardrooms across the United States, the same cliche questions are asked to prompt innovation: “What’s the next big thing?,” or, my least favorite, “Let’s think outside the box.”

To come up with answers to these cliches, executives look in the rear view mirror and rely on the same worn-out methods or, even worse, copy-the-competitor strategies. It’s no wonder that the resulting innovations aren’t innovations at all. They’re at best insignificant deviations from the status quo.

In contrast, Frazier’s contrarian “kill the company” exercise flips the innovation question upside down and forces executives to deploy new neural pathways. The strategy requires a radically new way of thinking that enables companies to see opportunities for innovation that may have been hiding in their blind spots.

Frazier’s strategy has another benefit that Adam Grant highlights in his book, The Originals:

This “kill the company” exercise is powerful because it reframes a gain-framed activity in terms of losses. When deliberating about innovation opportunities, the leaders weren’t inclined to take risks. When they considered how their competitors could put them out of business, they realized that it was a risk not to innovate. The urgency of innovation was apparent.

The “kill the company” exercise isn’t just for mega-corporations. You can employ variations of it in your own life by asking questions along the lines of the following:

Why might my boss fire me?

Why is this prospective employer justified in not hiring me?

Why are customers making the right decision by buying from our competitors?

In answering these questions, avoid superficial answers that treat them like that dreadful interview inquiry, “Tell me about your weaknesses,” which tends to induce humblebragging (“I work too hard”). Instead, really get into the shoes of the people who might fire you, refuse to hire you, or buy from your competitors.

Ask yourself: Why are they making that choice?

It’s not because they’re stupid. It’s not because they’re wrong and you’re right. It’s because they see something that you’re missing. It’s because they believe something that you don’t believe. And you can’t change that worldview or that belief by calling the same plays from the same old playbook.

Once you’ve got a good answer to these questions, switch perspectives like the Merck executives and find ways to defend against these potential threats.

Counterintuitively, the best way to catapult your life or your business might be to find ways to destroy it first.