The Director’s Chair is one of my favorite TV shows.

In each episode, director Robert Rodriguez interviews filmmakers about their craft. Learning about the creative process of brilliant directors helps inform my own approach to writing and storytelling.

In one episode, for example, Quentin Tarantino explains why he decided to buck conventional wisdom and structure movies in a non-chronological order to make them more interesting.

In another, Robert Zemeckis explains how a budget constraint forced him to scrap the original ending of Back to the Future that involved Marty sneaking into a nuclear test site to power up the time machine. This constraint—which Zemeckis says ended up being “the best thing that could have happened” to the film—instead led him to create a new ending with a lightning bolt striking the clock tower in the already built courthouse square.

The chances are that you’ve never seen these episodes—or heard of The Director’s Chair.

It’s because the show airs on an obscure television network called El Rey.

You won’t find it on Netflix.

It’s never been on any “trending now” lists.

It’s actually quite inconvenient to access the show. You have to affirmatively search for it and pay $2.99 per episode to watch it.

Yet I’ve gotten more out of that show than just about anything else I’ve watched this year.

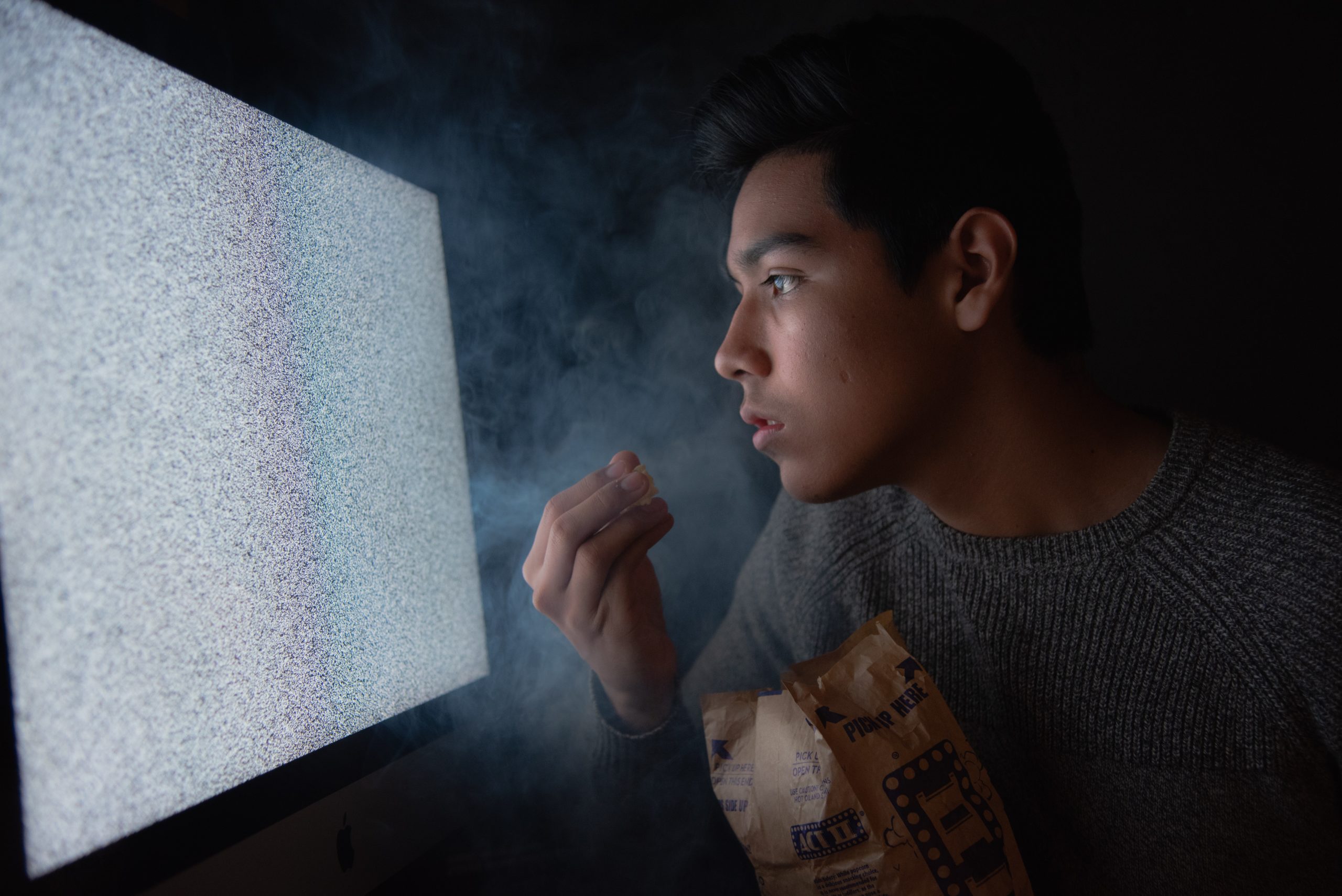

These days, we’re assaulted by a barrage of suggestions for media consumption tailored for maximum appeal by sophisticated algorithms. Instead of broadening our horizons, these algorithms cater to our supposed preferences. We can dig around for options off the beaten path, but our time and energy are limited. Instead, we jump right into the “most popular” list on Netflix and start binging Tiger King.

In many cases, we don’t even have to decide what to watch next. Our streaming services take that momentous burden off our shoulders by automatically queuing up a new show that the algorithms think we’ll love. Hello, Indian Matchmaking.

It goes beyond algorithms to every convenient shortcut. In the face of an overwhelming deluge of content, we turn to Top 10 lists, blockbusters, and bestsellers. As a result, the breadth of our inputs dwindles and our intellectual vista narrows.

In a different era, radio DJs had control over the songs they played. Not anymore. Now, they pick from a carefully curated list of songs predetermined to be the next big hit.

We’re being intellectually castrated, but we’re not even aware of it.

Escaping this tyranny of convenience requires being intentional about what you consume—and making your own choices instead of letting others choose for you.

This, in turn, requires you to answer simple questions that most algorithm-nurtured people find exceedingly difficult to answer: What do I actually want to learn? What am I—not other people—interested in?

Have you always wanted to learn more about country music (Ken Burns has an excellent documentary about that). Do you want to know why our education system is broken and how we can fix it? (Read the 1971 book Teaching As a Subversive Activity). Do you want to learn more about the creative process of people outside your field? (This was the search that led me to Director’s Chair).

Once you’ve figured out what you want to learn, turn to less flashy sources of information. Look where no one else is looking. Haruki Murakami had it right: “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

Search for groundbreaking ideas that have yet to break through. Academic papers on the cutting edge. Movies that have fallen out of mainstream awareness. Once-influential books now out of print— the type of books you can find only in libraries and used book stores, not on Kindle Unlimited.

If you stick to the convenient, you’ll never find the unexpected.

It’s only through the inconvenient and the unfashionable that you’ll find diverse inputs that will expand your thinking and spur your imagination.

Bold