Dick Fosbury couldn’t stand still.

He was rocking back and forth, wiggling his fingers, eyeing the bar from a distance, and calculating the physics of his anticipated leap, while 80,000 fans watched with held breath.

He began his confident jog toward the bar, concealing the storm brewing underneath.

It was the 1968 summer olympics in Mexico City. And Dick Fosbury, a 21-year-old from the middle of nowhere in Oregon, was seconds away from changing the Olympic high jump forever.

If you met Fosbury in person, you wouldn’t think that he was an athlete. He was awkward, scrawny, and tall, with a significant acne problem that he couldn’t seem to shake off.

When Fosbury was training to be a high jumper, athletes would use a technique called the straddle method, where they would jump face down over the bar. But the straddle never worked for Fosbury. As a high school sophomore, he could clear only a 5’4” bar, which put him at the same level as junior high athletes.

In other words, a life of participation trophies awaited him.

The story could have ended here. But on a bus ride to a track meet in Grants Pass, Oregon, something happened that shook Fosbury out of his mediocrity.

At the time, the straddle method was considered beyond improvement. It was the method used by the best high jumpers. There was no need to experiment or come up with something new.

But Fosbury was no ordinary athlete. He was a contrarian. He prided himself on disrupting conventional wisdom, taking risks, and exploring new possibilities.

At the Grants Pass track meet, as he faced a 5’6” bar–two inches higher than his personal best–he knew had to do something radically different to stand a chance.

He realized that the rules allowed the athlete to clear the bar any way they wanted as long as they jumped off of one foot. So, instead of jumping face down to the bar like everyone had done before him, he jumped backwards and cleared the 5’6” bar with ease.

Gaining confidence in his new technique, he tried again and cleared 5’8”. He set a new personal best that day in Grants Pass by clearing 5’10.”

In a sport where an increase of a fraction of an inch is sufficient to prompt celebratory pats on the back, Fosbury advanced his jump in a single day by a whopping six inches.

Fosbury continued to perfect his backwards jump, resulting in dramatic improvements in performance. By his senior year, he could clear 6’5½”.

Despite these dramatic improvements, his seemingly haphazard approach invited ridicule. A newspaper called him “The World’s Laziest High Jumper.” Many of the fans watching him often laughed at him as he cleared the bar like a fish flopping in a boat. To his coaches, the Fosbury flop–as it came to be known–was an outrageous and dangerous departure from well-established norms. They tried to convince Fosbury to drop the flop.

Ignoring the naysayers, he kept gradually improving his technique. He won the NCAA Championship and earned himself a spot on the 1968 Olympic team.

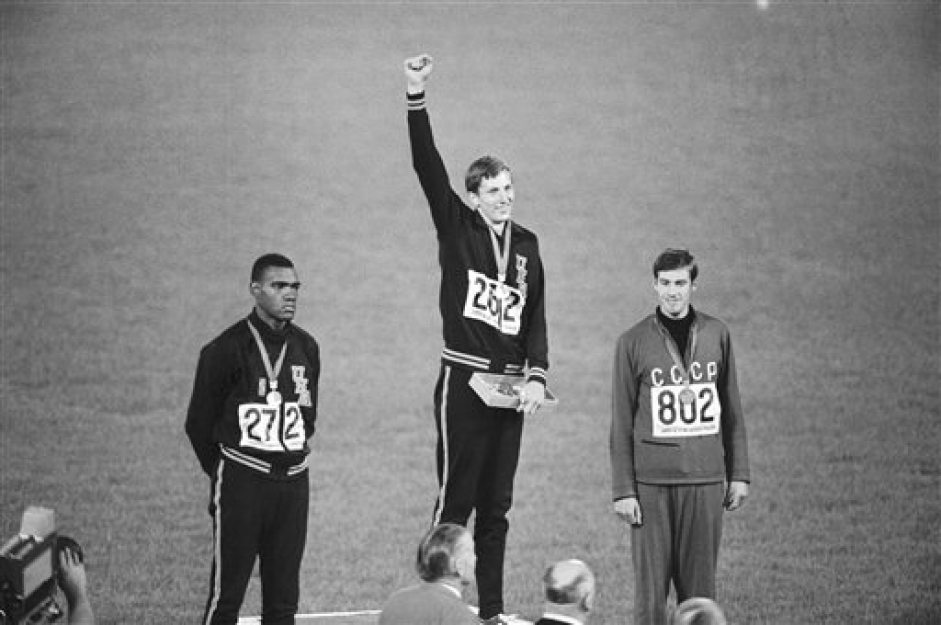

The laughs eventually turned into cheers as Fosbury proved his critics wrong and took home the gold medal at the Olympics—by doing the exact opposite of what everyone else was doing. The Fosbury flop is now the standard method used by high jumpers.

The transformation of Dick the mediocre teenage athlete to Dick Fosbury the high-jump revolutionary holds important lessons for us all.

1. It often takes a beginner’s mind to enable revolutionary changes.

The experts assumed that in an event as ancient as the high jump, innovation was not possible. Even if it were, it would not come from a 15-year-old pimply faced mediocre high jumper who struggled with the straddle technique.

But that’s precisely what made Fosbury ideally situated to revolutionize the high-jump. As a beginner, Fosbury had no stake in the straddle method. It didn’t work for him, so he had no reason to stick with the status quo.

The Japanese call this shoshin or beginner’s mind. When you remain open to the possibility that there is no good reason for the status quo, you’ll be in a better position to change it.

2. If you do anything new, the world will try to beat you into conformity.

After Fosbury started making waves with his flop, he won a small scholarship to attend Oregon State. His coaches advised him to drop the flop and return to the clearly superior straddle method. The result was a disaster. Fosbury’s jump regressed more than a foot.

He then defied the authority figures in his life and went back to his flop. He maintained his distinctive jump, and worked on perfecting it, the world be damned. Even though Fosbury wasn’t the first person to try the backward jump–another high school athlete in Michigan had used it a few years prior–only Fosbury had the grit to persist in the face of the prevalent pressures to conform.

Fosbury’s coach relented only after Fosbury jumped 6’10” using his flop, breaking the Oregon State record. He pulled Fosbury aside and said “I’m not sure exactly what you’re doing, but it’s working for you. So stick with it, I guess.”

And stick with it, Fosbury did. When he cleared one bar after the next in the 1968 Summer Olympics, the laughs that initially followed from the stands soon turned into cheers. After he won the gold, he came home to a ticker-tape parade and appeared live on the Tonight Show, where he taught Johnny Carson and Bill Cosby how to perform the Fosbury flop.

3. You must be willing to fail.

Fear of failure is the primary reason why most of us are afraid to disrupt conventional wisdom. In the face of tension and uncertainty, we retreat to the comforting embrace of the status quo.

What if this doesn’t work?

What if my teammates point and laugh?

What if I make a fool out of myself in front of my coaches?

Better stick with the default.

The “fail fast” mantra is all the rage these days in Silicon Valley, and many entrepreneurs view failure as a necessary evil on the road to riches.

But failure isn’t an evil at all. It’s a prerequisite to doing anything different or original. If you’re not prepared to be wrong or to fail, you’ll be stuck with the status quo.

The Fosbury flop could have been a colossal flop, but Dick was willing to take that risk.

4. You must offer a viable alternative

To Fosbury, being a contrarian wasn’t just about disrupting the status quo. He didn’t simply stand on the sidelines, rub his chin, and criticize the straddle method.

Rather, he revolutionized the status quo by offering a better alternative.

5. Contrarian thinking can be a super power

The ability to disrupt established methods and find new ways of looking at old ideas is one of the most sought-after qualifications in all fields. It’s a super power that allows you to be right when others are wrong.

To Fosbury, the field of face-first jumpers was too crowded. He knew he could get ahead only by doing something radically different. He abandoned the center, moved to the fringes, and quite literally flipped the high-jump script to unleash a super power in the form of his flop.

And the high jump has never been the same again.

[The facts in this article are based on Richard Hoffer’s book, Something in the Air: American Passion and Defiance in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.].

Bold