I get the same feeling every time I sit down to write.

I don’t feel like it today.

I’m just not inspired.

I have writer’s block.

I feel exhausted. I should just take it easy and answer some emails.

But then I ask myself.

Do cardiac surgeons look for inspiration before they conduct open-heart surgery?

Do commercial pilots say, “I won’t be flying today. I have a bad case of pilot’s block.”?

No. They sit down and do the work.

We talk about writer’s block as if it’s the common cold you caught.

“I’ve had writer’s block for the past week. It’s terrible,” we lament.

Writer’s block is a myth. It’s a euphemism for procrastination. It’s a convenient excuse that we generate to avoid the work we’re supposed to do.

You don’t have to be a writer to experience it. If you dared to do anything outside of your comfort zone, you’ve experienced what Steven Pressfield calls “Resistance” in his wonderful book, The War of Art.

Resistance is like the Alien or the Terminator or the shark in Jaws. It cannot be reasoned with. It understands nothing but power. It is an engine of destruction, programmed from the factory with one object only: to prevent us from doing our work.

Most of us lead two lives.

There’s the life we’re currently living. In this life, we drop our new year’s resolutions. We have goals, but we don’t reach them, let alone attempt them. We buy books, but don’t read them. We buy a treadmill, but let it gather dust in the garage.

Then there’s the version of our best self that’s on the horizon somewhere. He exercises, meditates, and eats well. She runs for political office, starts a non-profit, launches a business, becomes a high-powered lawyer, or finally writes that book.

What stands between these two selves is Resistance–that mystic force that’s out to prevent you from doing the work you’re supposed to do.

The good news: You’re not alone. No one is immune to resistance–not even seasoned professionals.

Even when he was 75, Henry Fonda, whose acting career spanned more than five decades, would throw up in his dressing room before every single performance.

What’s important is what he’d do next.

He’d clean himself up, drink some water, march on stage, and start doing his job.

Fonda was a professional. He experienced resistance like the rest of us, but he knew the secret to overcoming it: Just start.

Once Fonda began performing his craft, the resistance would slip away. He’d marvel audiences and show up the next day to do the same. Rinse and repeat.

This isn’t all that different from diving into a cold pool. At first, resistance takes over. You look at the pool, walk towards it, and walk away. You tell yourself, “I’ll get some sun first before jumping in.” You march toward the pool again, dip your toes, and back off because it’s too damn cold.

If Henry Fonda were alive today, he’d tell you to jump. Just jump.

After you jump in and start swimming, it will get easier. The water will get warmer. Euphoria will take over. You will be proud of yourself.

The longer you wait to confront resistance, the harder it gets.

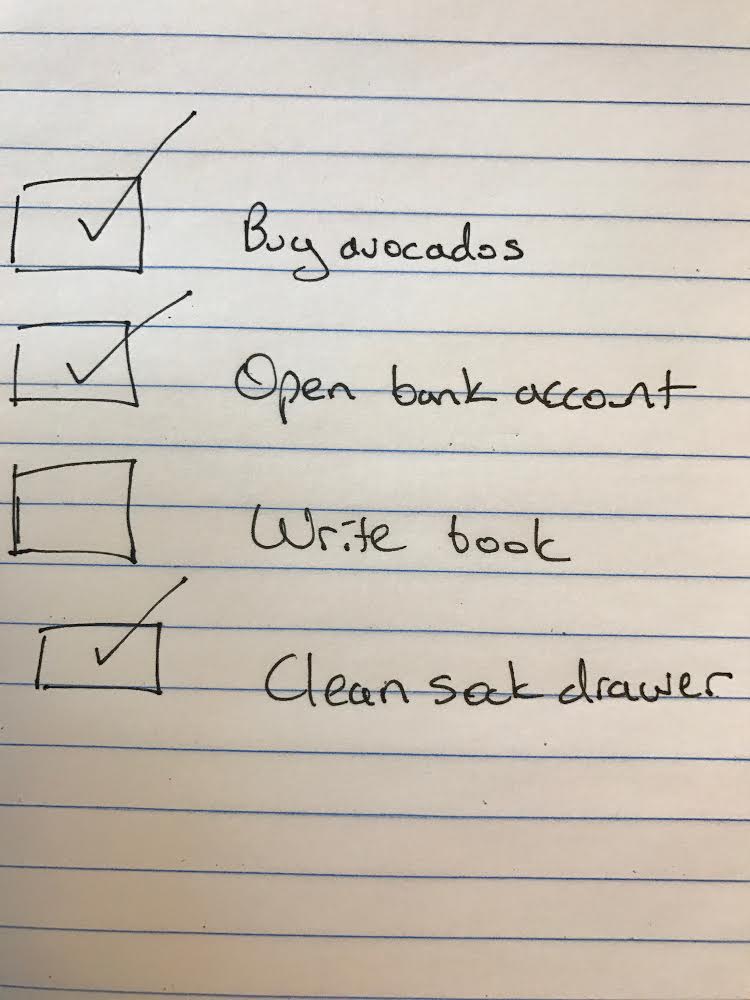

Resistance, when ignored, doesn’t stay dormant. It starts doing push-ups. That major life project that’s been languishing on your to-do list becomes harder and harder to tackle at each time you look at it but choose to clean your sock drawer instead.

Sir Isaac Newton had it right with his first law: Objects in motion tend to stay in motion.

Once you get going, it’s easier to keep going.

Starting is the hardest part.

But even after you start, you must remain vigilant. Here’s Pressfield again:

The danger is greatest when the finish line is in sight. At this point, Resistance knows we’re about to beat it. It hits the panic button. It marshals one last assault and slams us with everything it’s got. The professional must be alert for this counterattack. Be wary at the end.

This very moment, you have a choice.

You can give in to Resistance and keep reading your emails or browsing the web.

Or you can sit down, do the work that you’re meant to do, and put Resistance to shame.

Your turn.

Bold