“Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

― Abraham Lincoln

Political discourse has taken a particularly nasty turn. We use words normally reserved for mortal enemies to describe our political adversaries. Some of the choice terms thrown around in the last U.S. presidential elections include “crooked,” “nasty,” “a basket of deplorables,” and “homegrown demagogue.”

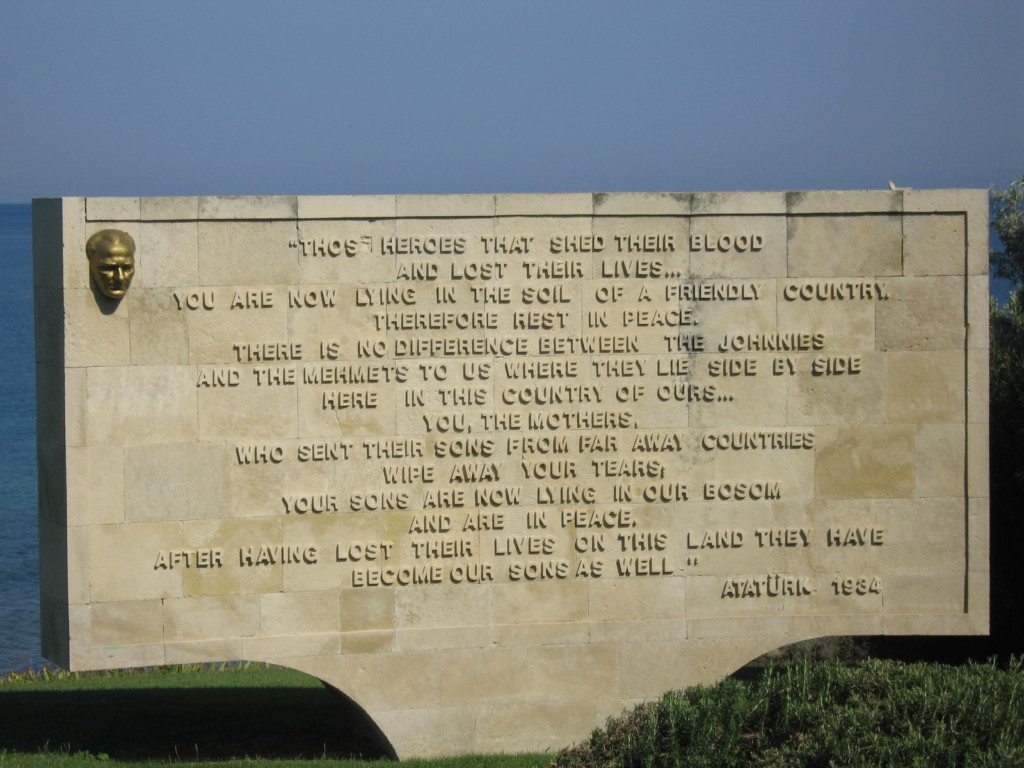

Compare these words to those in a letter penned in 1934 by Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. The letter was addressed to the mothers of Australian soldiers who lost their lives battling the Turks on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War I. Ataturk himself was a commander in Gallipoli and fought the Australians. The battle in Gallipoli was vicious. It claimed the lives of nearly 9,000 Australians and over 80,000 Turks.

Given the bloody conflict and the monumental death count, one might expect the Turks and the Australians to bear a deep-seated resentment toward each other, at least in the immediate aftermath of the war. But, within two decades of the Gallipoli battle, Ataturk offered the Australian mothers the following heartfelt consolation. For context, note that “Johnnies” refers to the Australian soldiers and “Mehmets” refers to the Turkish soldiers.

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives…

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours.

You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears.

Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace.

After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.

Ataturk’s letter, inscribed on a memorial in Gallipoli, Turkey

The sentiments in Ataturk’s letter are subversive.

Most modern politicians wouldn’t dare to use similar words to describe their political opponents, let alone enemies that killed tens of thousands of their own people.

We believe that our enemies are to be vilified, not heroized, and to be rejected, not embraced, certainly not as “our sons.” Although the authenticity of Ataturk’s letter has recently been called into question, the underlying sentiment accurately describes his feelings at the time, as evidenced by his other statements on the topic.

Of course, Ataturk had self-serving reasons for expressing these evocative sentiments toward the Australians. The advancement of his newfound nation required engagement with the West and engagement required letting bygones be bygones.

I recalled Ataturk’s speech after watching a recent video interview with Amaryllis Fox, a former CIA counter-terrorism officer (see the video at the end of the post). Using words that harken back to Ataturk’s letter, Fox underscores the value of listening to your enemy: “The only real way to disarm your enemy is to listen to them,” she argues. “If you hear them out, if you’re brave enough to really listen to their story, you can see that more often than not you might’ve made some of the same choices if you’d lived their life instead of yours.”

To be sure, Fox’s advice isn’t always tenable. You can’t sit down to have a policy discussion with a group like ISIS who uses violence as an end in itself to create a pure set of believers.

But, in many cases, the underlying sentiment is correct. Instead of getting blinded by our own rage against our enemies, we’re often better served by engaging with them and realizing that many of the problems that fuel modern conflicts are beyond the capacity of bombs to resolve.

Otherwise, as Fox puts it, this never ends.

Bold