Drew Dernavich is one of the best cartoonists of all time.

In 2006, he was selected the country’s top magazine cartoonist and awarded the National Cartoonists Society award.

Back in the day, before cartoonists started making digital sketches, Dernavich was drawing cartoons the old-fashioned way—with a sharpie and paper.

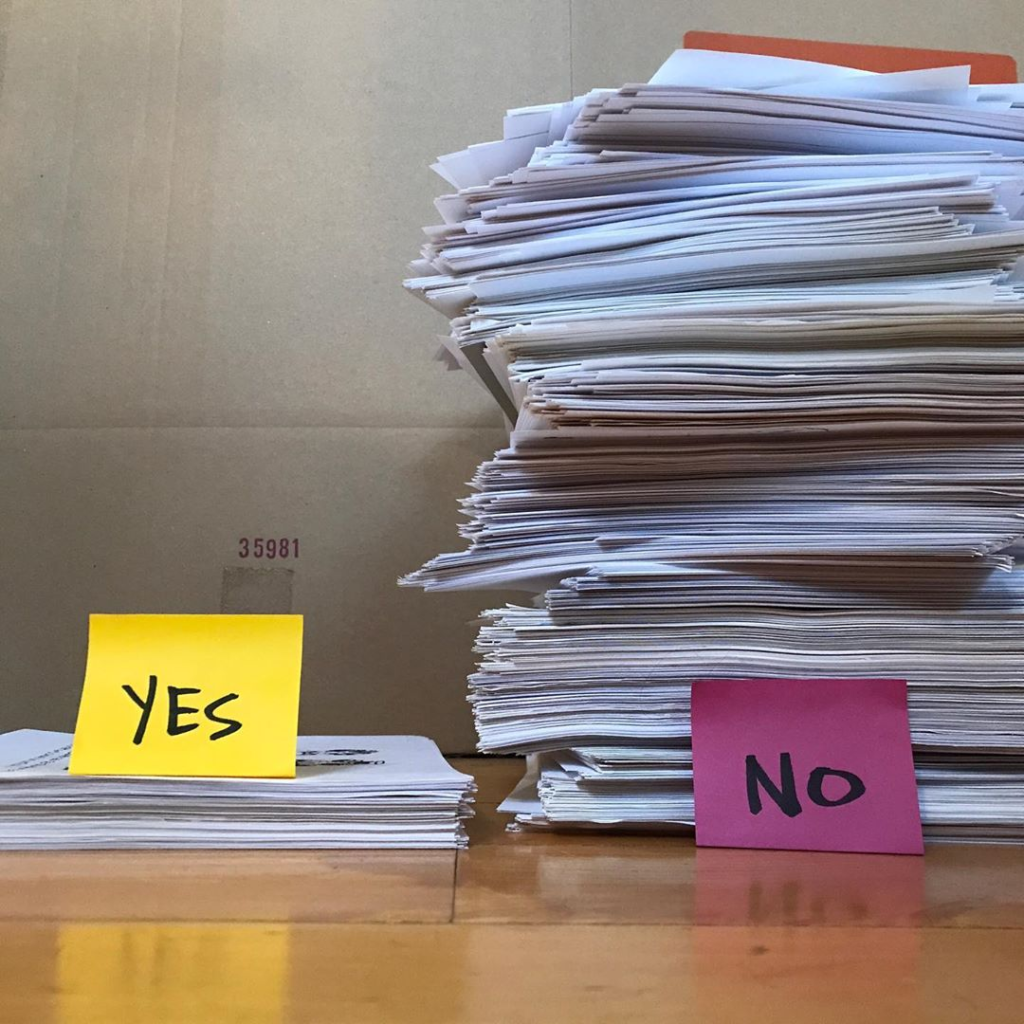

A few years ago, when he was cleaning his house, he decided to organize his old, hand-drawn cartoons and divided them into two piles: the “yes” pile for the published ones and the “no” pile for the rejected ones.

Here’s what the piles look like:

The lesson is universal: Good ideas often follow bad ideas.

“When it comes to idea generation,” Adam Grant writes, “quantity is the most predictable path to quality.” Innovative thinkers fail a lot because they try a lot.

For example, writers for the satirical news publication The Onion propose roughly 600 headlines every week. Only 18 get selected—a 3 percent success rate. The ones that make the cut are truly hilarious (“Drugs Win Drug War” or “Buddy System Responsible for Additional Death.”).

At X, Google’s moonshot factory, the embrace of bad ideas is built into the culture. X doesn’t innovate for Google. X’s mission is to create the next Google. From time to time, Xers hold a “bad idea” brainstorm where people are encouraged to share terrible ideas out loud (One failed suggestion was “a fuel cell implanted in the body, powered by body fat.” This would have solved two problems simultaneously: limited battery life for your iPhone and obesity).

This practice might strike you as odd—why waste time brainstorming bad ideas?—but X is onto something. “You can’t get to the good ideas without spending a lot of time warming up your creativity with a bunch of bad ones,” X’s head Astro Teller explains. “A terrible idea is often the cousin of a good idea, and a great one is the neighbor of that.”

This principle also makes it easier to get started. It’s hard to stare at a blank page trying to think up good ideas. But if your goal is to generate bad ideas—and we’re all masters at that—it’s much easier to put pen to paper (or hand to keyboard).

Terrible ideas don’t magically become great. Failing fast is meaningless—unless you’re also learning fast. Dernavich, for example, doesn’t accuse the editors of failing to see the genius in his rejected cartoons. Rather, he places the blame squarely in himself: “These were rejected for good reasons. A lot of them are dated, unfunny, and potentially in bad taste.” He learned why the bad ones flopped and learned how to make better cartoons.

Dernavich’s rejections continue to pile up. “I’m still generating a lot of crappy rejected ideas,” he writes. “They’re just in digital form now!”

Whether analog or digital, the principle remains the same: The road to breakthrough ideas is paved with bad ideas.

Accept that many of your ideas are going to be bad. Don’t sit around waiting for the “perfect” idea to arrive (spoiler: there’s no such thing). Hold your own bad idea brainstorming session for your next product launch or generate 10 bad headlines for your next blog post.

You’ll be surprised where they lead.

Bold