In my email last week (“I see you”), I wrote about Sawubona, a typical Zulu greeting that literally means “I see you.” It refers to seeing in a more meaningful sense than the simple act of sight. It means, “I see your personality. I see your humanity. I see your dignity.”

The email generated terrific responses from so many of you. The word empathy was a recurring theme in your responses, which inspired this email about empathy—specifically about how empathy can backfire.

To show empathy means to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and feel their pain or suffering. If someone finds themselves stuck in a hole, empathy allows you to climb down into that hole and share their experience. President Barack Obama blamed an “empathy deficit” for many of the problems plaguing social discourse in America.

To some extent, research backs up this sentiment: Studies show that empathy for members of a stigmatized group can reduce prejudice, and empathy for racial and ethnic groups can produce support for civil rights measures.

Put simply, empathy is good.

But much of what we believe about empathy turns out to be wrong, according to new research that hasn’t become mainstream.

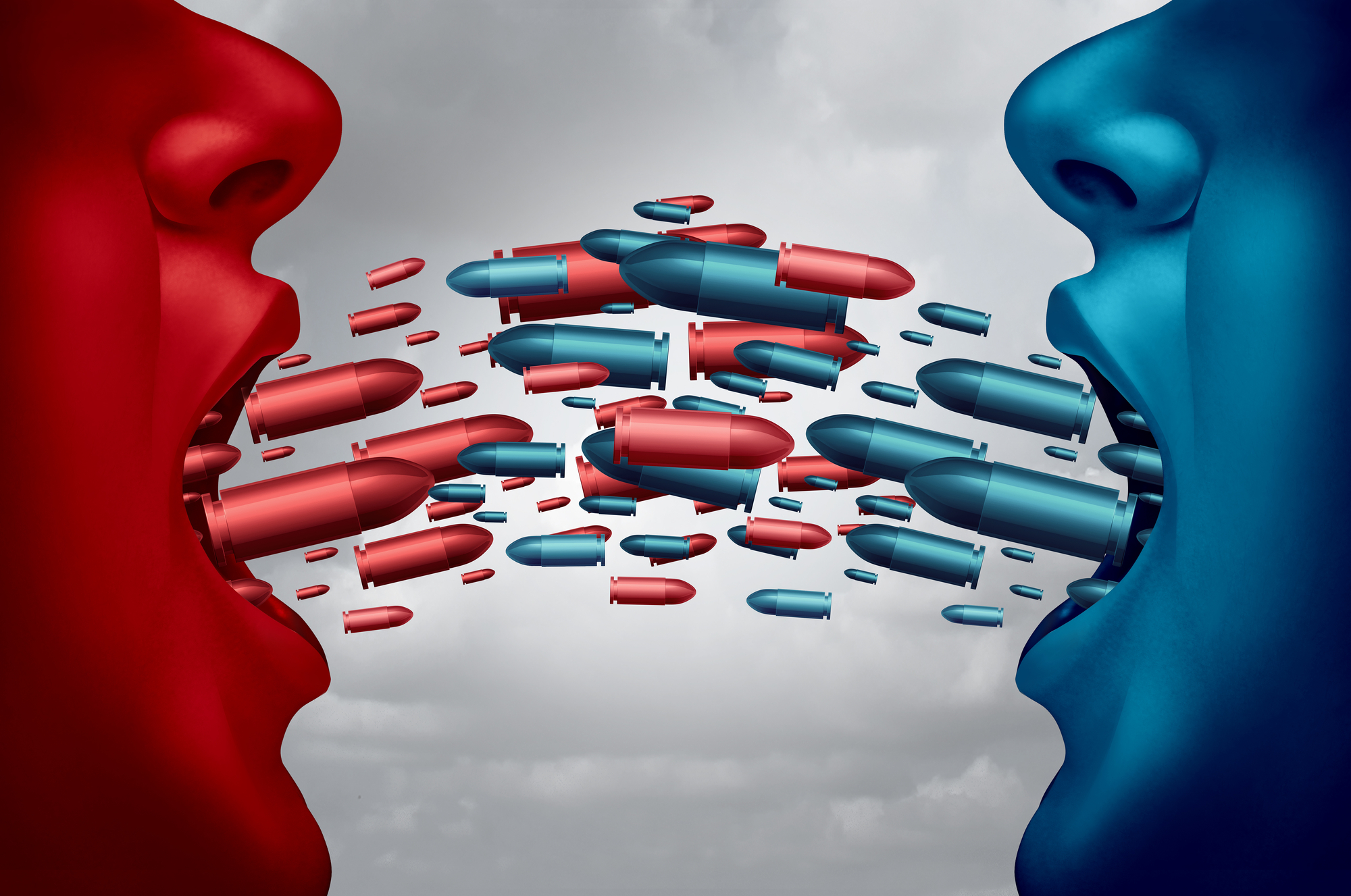

This research, backed up by several prominent psychology and political-science studies, suggests that empathy can backfire. People are biased in their expression of empathy. They feel empathy toward members of their own group but not toward members of other groups, creating what researchers call an “empathy gap.”

For example, one study, published in the prestigious American Political Science Review, found that “empathic concern does not reduce partisan animosity in the electorate and in some respects even exacerbates it.” (emphasis mine).

In the study, researchers measured the participants’ empathy levels by asking them whether they agree or disagree with a series of statements (e.g., “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.”). They discovered that people who scored high on the empathy scale had more negative feelings toward political opponents. High-empathy people were also more likely to support efforts to censor a controversial speaker from the opposing party. They even expressed greater delight when an audience member who was there to hear the speech was struck by a student protesting the speech.

The problem, then, isn’t a lack of empathy. The problem is how we experience empathy. The members of our own team get empathy. Others get a punch to the gut. We belittle them (“I told you so”). We ostracize them (“If you’re not with us, you’re against us.”). We ridicule them (“What an idiot”).

We reject people who don’t follow our norms.

We reject people who have a different perspective.

We then reject people who don’t reject the right people.

We argue with each other, not in an attempt to persuade, but to signal. Abortion is murder. My body, my choice. We don’t make these arguments to convince our opponents that we’re right. We make them to convince our own group that we belong. Arguments, in other words, have turned into membership cards that we wave on social media to make sure everyone knows what team we play for.

Although technology has torn down some barriers, it has erected others. We’ve been algorithmically sorted into echo chambers. Even on the rare occasions that opposing views make it to our internet feeds, it’s easy to disconnect from them. Simply unsubscribe, unfollow, or unfriend.

As our echo chambers get louder and louder, we’re repeatedly bombarded with ideas that reiterate our own. When we see our own ideas mirrored in others, our confidence levels skyrocket and our understanding of the full picture plummets. Opposing beliefs are nowhere to be seen, so we assume that they don’t exist or that those who adopt them must be out of their minds.

The cure isn’t more empathy. Rather, the cure is to extend empathy toward members of other groups, by seeing the us in them.

We can become curious about someone else’s view without trying to convert them to our own.

We can drop our black-and-white arguments and delight in the nuanced shades of grey.

We can engage with others even when we don’t endorse all of their actions.

We can resist attempts to slice and dice us into groups and sub-groups.

We can remind ourselves that beauty thrives in diversity—and that includes diversity of thought.

Above all, even in the face of disagreement, we can invoke our deepest human impulses and respond with compassion and curiosity rather than animosity.

Bold