Think back on the failures you’ve had in your life.

If you’re like most people, you’ll picture the bad outcomes—the business that never took off, the penalty kick you missed, or the job interview you bombed. Poker players, as Annie Duke explains in Thinking in Bets, refer to this tendency to “equate the quality of a decision with the quality of its outcome” as “resulting.” But, as Duke argues, the quality of the input isn’t the same as the quality of the output.

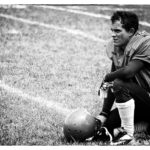

It’s possible for good decisions to lead to bad outcomes. In conditions of uncertainty, outcomes aren’t completely within your control. An unlucky draw can screw up a perfectly played poker hand. A strong wind can misdirect a beautifully shot soccer ball. A hostile judge or jury can derail a great case.

If we engage in resulting, we reward bad decisions that lead to good outcomes. Conversely, we change good decisions merely because they produced a bad outcome. We start shaking things up, reorganizing departments, or firing or demoting people. As one study shows, National Football League (NFL) coaches change their lineup after a 1-point loss, but don’t change it after a 1-point win—even though the difference between the two is negligible.

In our own lives, most of us act like American football coaches, treating success and failure as binary outcomes. But we don’t live in a binary world. The same decision that produced a failure in one scenario can lead to triumph in others. “Failure hovers uncomfortably close to greatness,” wrote Paul Watson, the co-discoverer of DNA’s double-helix structure.

For the vast majority of my life, I ignored the advice I’m shelling out here. After a mistake in a blog post, a botched question in a podcast interview, or a slip-up during a speaking engagement, I would beat myself up. My inner critic would roar to life whispering such pleasantries as You’re a failure or You should have spent more time preparing for that talk.

Over time, I learned to pivot from the outputs to the inputs (I’m still a work-in-progress). When I fail at something, I first ask myself, “What went wrong with this failure?” If the decisions I made need fixing, I fix them. But I also ask: “What went right with this failure?” I retain the good-quality decisions, even if they produced a failure.

Failure has a way of distorting our vision. You often have to take the lenses off—by pivoting your focus from the seemingly awful outcome to the inputs—in order to see clearly.

Bold