When Steve Martin first started performing stand-up comedy, there was a proven formula for telling jokes. Each joke came with its own cringeworthy punchline.

Here’s an example:

How does NASA organize their company parties? They planet.

But Martin wasn’t satisfied with the standard formula. It bothered him that the laughter following a punchline was often automatic. Like Pavlov’s dogs salivating at the sound of a bell, the audience would instinctively laugh when the punchline was delivered. What’s more, if the punchline didn’t produce laughter, the comedian would stand there, embarrassed, knowing his joke had bombed. Punchlines were a lousy way of doing comedy, Martin thought, both for the comedian and the audience.

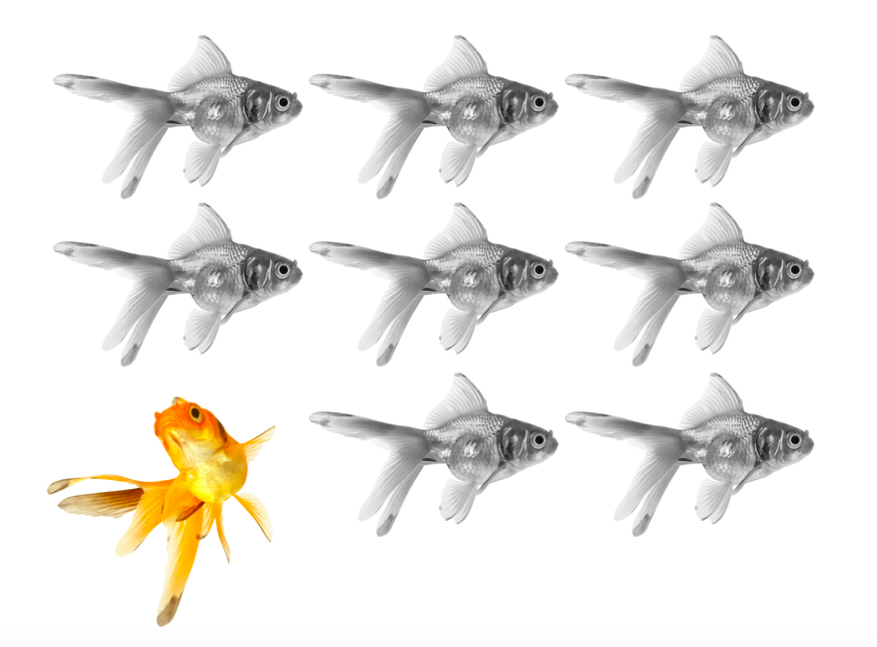

Martin asked himself, “What if there were no punchlines? What if I created tension and never released it?” Instead of conforming to audience expectations, he decided to violate them. He believed that, without a punchline, the resulting laughter would be stronger. The audience would laugh when they chose to do so, without being triggered by a gimmick.

Martin then did what all great scientists do: He tested his idea. One night, he went onstage and told the audience that he was going to do the “Nose on Microphone” routine. He methodically proceeded to place his nose on the microphone, stepped back, and said “Thank you very much.”

There was no punchline, so the audience sat in silence, stunned by Martin’s departure from conventional comedy. But the laughter arrived when the audience caught up to what Martin had done. Martin’s goal, in his words, was to leave the audience “unable to describe what it was that had made them laugh.” The state would be like “the helpless state of giddiness experienced by close friends tuned in to each other’s sense of humor, you had to be there.”

The initial response to Martin’s approach was ridicule. One critic, sticking to the stand-up comedian’s playbook, wrote: “This so-called ‘comedian’ should be told that jokes are supposed to have punchlines.” Another described Martin as “the most serious booking error in the history of Los Angeles.”

That most serious booking error quickly became the most profitable one. The path Martin followed proved Max Planck right: The ridicule was followed by discussion, which was followed by adoption. Audiences and critics eventually caught up, and Martin became a stand-up legend.

What in your own world is the comedic punchline—an unnecessary relic of the past clouding your thinking and hampering forward progress? What do you assume you’re supposed to do simply because everyone around you is doing it? Can you question that assumption and replace it with something better?

We used to assume that a restaurant required tables, an immobile kitchen, and a brick-and-mortar location. Questioning these assumptions gave us food carts. We used to assume that late fees and physical stores were necessary for video rentals. Questioning these assumptions gave us Netflix. We used to assume that you need bank loans or venture-capital funding to launch a new product. Questioning these assumptions gave us Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

“Your assumptions are your windows on the world,” as Isaac Asimov put it. “Scrub them off every once in a while, or the light won’t come in.”

[Inspiration: Steve Martin, Born Standing Up].

Bold